I recognised myself in a framework about family communication styles. Not the comfortable one. I’m number five on Virginia Satir’s list. The one who says the thing as I see it. The one who watches family members shift in their seats. The one friends call honest when they’re generous, blunt when they’re not.

This recognition came from reading about Satir’s work. Virginia Satir was an American psychotherapist, often called the mother of family therapy. She worked with whole families, not isolated individuals.

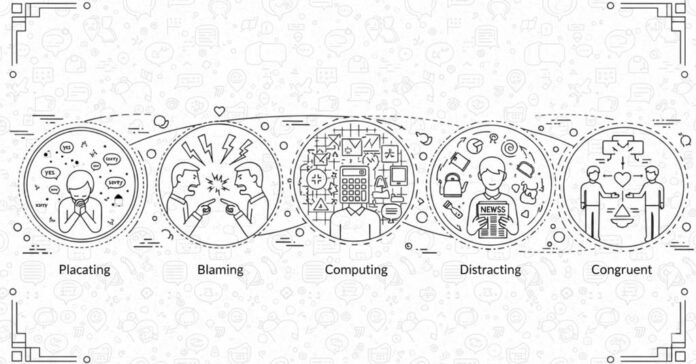

Her approach fed what later became structural family therapy. Born in 1916 in Wisconsin, she founded the first family therapy training programme. The bit that caught me was simple. She identified five patterns people fall into when stress arrives:

- Placating: Going along to get along. Saying what others want to hear. Apologising constantly. Keeping peace at any cost.

- Blaming: Pointing fingers. Finding fault. Proving you’re right and they’re wrong. Accusatory and self-righteous.

- Computing: Staying hyper-rational. Keeping emotions locked away. Speaking from the head, never the heart. Facts over feelings.

- Distracting: Changing the subject. Making jokes. Bringing up irrelevant information. Anything to avoid the uncomfortable topic.

- Congruent: Words match feelings match body language. Speaking directly. Owning what you feel. No disguising, no pretending.

I decided to hold each pattern against what I actually see. At my kitchen table. In my friendships. At work, when things get uncomfortable. This is observation, not therapy. I write to think. I’m willing to be wrong.

Placating

Saturday’s plan gets discussed at dinner. Again. Third time this week. The quietest person at the table says yes. Fine. Whatever works. Smile doesn’t reach the eyes, but nobody’s checking.

I’ve watched my kids do this. Take my daughter, the middle child, when she was young. Already learned to read the room and edit her needs before speaking. When her brother wants pizza and she wants pasta, she says, “Pizza’s fine.” Voice goes softer. Shoulders drop slightly. The family moves on, crisis avoided.

Except there’s no crisis to avoid. Just a preference about dinner.

This pattern shows up everywhere in family communication styles. The placater thinks they’re being generous. They’re actually being silent. The cost is incurred later, with compound interest. Small yeses build into bigger resentment. Then, on one Tuesday, something minor happens, and the explosion makes no sense to anyone watching.

I notice it in myself too. Especially when I was married, I gave in to my ex for peace. Easier to say yes than face the tension. The wobble felt worse than the compromise. That calculation was almost always wrong.

Try this: Ask someone their preference once. Then wait ten seconds. Don’t fill the silence. Don’t offer options. Don’t reassure them; it doesn’t matter. Just wait. See what shows up when the room gets quiet.

Blaming

Kitchen conversations that sound like courtroom cross-examinations. Who started this? You did. Who made it worse? Also you. Who’s right? Obviously me.

I’ve seen this more in past work environments than at home. A colleague sends an email listing everything that went wrong. Each sentence points at someone else. Never at themselves. The tone isn’t seeking solutions. It’s building a case. Assigning blame. Establishing innocence.

Blaming feels productive because it’s decisive and quick. There’s a weird satisfaction in being correct about someone else’s failure. No heavy lifting required. No vulnerability. No admission that I might have contributed to this mess, too.

But watch what happens to family communication styles when blame becomes the default. Nobody shares problems early. Everyone hides mistakes. The person who messed up spends energy covering tracks instead of fixing issues. Trust evaporates.

I catch myself here more than I’d like. Especially when I’m defensive. The finger points outward automatically. It’s protection masquerading as clarity.

Try this: Next time you’re building a case against someone, stop halfway through. Ask yourself what you’re afraid of. Not what they did wrong. What are you protecting by making them wrong? Then ask one question that starts with ‘how’ or ‘what’ instead of ‘why’.

Computing

Facts. Data. Logic. Reason. The head does the talking whilst the heart stays locked in the basement.

I know this one intimately. My child asks why they can’t go to their friend’s house. I respond with schedules, commitments, prior agreements, and rational explanations. All true. All carefully constructed. All are missing the actual point.

What’s needed isn’t a logical case. It’s understanding the disappointment.

Computing feels safe. Emotions are messy and unpredictable. Facts are clean. You can arrange them. Stack them. Build arguments that feel solid. The temperature in the room drops, but at least nobody’s crying.

The computing style in family communication styles creates distance without solving anything. The other person feels unheard. Not because your facts are wrong. Because facts aren’t what they needed.

Another child once told me I sound like a textbook when I’m uncomfortable. Completely right.

Try this: Next time you reach for facts to explain your position, add one feeling. Not ‘I feel that we should…’ That’s still logic wearing a disguise. Actual feeling. ‘I’m worried this will spiral’ or ‘I’m frustrated we’re here again’. One sentence. Then stop talking for ten seconds.

Distracting

The kettle needs filling. Email notification. The weather’s getting cold. Did you see that match? Quick joke. New topic. Another joke. Oh, look, the dog needs walking.

The art of leaving the room without moving. The subject changes before the complicated conversation starts. Or right when it’s getting uncomfortable. The distractor isn’t necessarily trying to avoid. Sometimes they don’t even notice they’re doing it.

My BFF does this brilliantly. We’re talking about something real, something that matters, and suddenly we’re discussing whether pineapple belongs on pizza. Ten minutes later, I can’t remember what we were initially discussing. The tension’s gone. So is the connection.

Distracting looks like being upbeat. Keeping things light. Not dwelling on problems. We praise this in British culture. But amongst family communication styles, it’s not light. It’s avoidance. The heavy thing doesn’t disappear. It waits. Gets heavier.

Try this: When you feel the urge to change subject, don’t. Name what you’re avoiding in one sentence. ‘I want to talk about anything except this right now. ‘ Then set a timer for two minutes. Hold the thread until the bell rings. Two minutes. That’s it.

Congruent

This is where I live. Number five. The one where words, feelings, and body language match. Say what you see. Own what you feel. Looks like you mean it.

Sounds noble when typed. In real life, it can land hard. People I care about have told me my honesty comes across as a push. They’re not wrong.

My truth doesn’t come with cushions. When I’m frustrated, I say I’m frustrated. When something doesn’t make sense, I say it doesn’t. My face shows what I’m thinking before my mouth catches up. That’s supposed to be the healthy option in family communication styles. Satir called it congruent. Authentic. Direct.

But directness without wisdom is just bluntness with better PR.

I’m learning something slowly. Being right isn’t the same as being useful. Saying exactly what I think isn’t always what the moment needs. Sometimes timing matters more than truth. Sometimes the truth can wait ten seconds whilst I think about how it’s going to land.

Still say what I see. But now I also name the limit of my view. Here’s what I’m reading from this situation. Here’s what worries me. Here’s what I’m asking for. Then the new bit: actually listen.

The listening part is new. I used to think that saying the truth was enough. Job done. Move on. Turns out that’s only half of congruent communication. The other half is making space for someone else’s truth without already building my response while they’re still talking.

Try this: Say the truth in one clear sentence. Then ask, ‘What lands badly about that?’ And mean it. Actually want to know. Don’t defend. Don’t explain. Just listen to what comes back.

Friends and colleagues

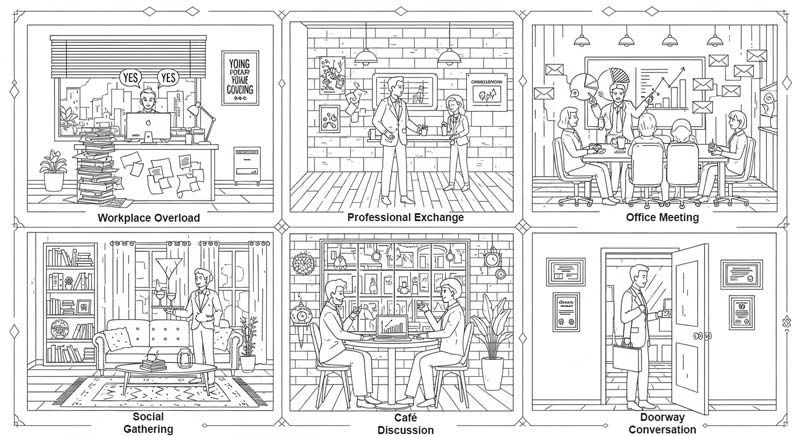

These patterns aren’t just family communication styles. They leak everywhere.

The placater at home becomes the colleague who says yes to every request. Never pushes back. Never name a boundary. Reliable until they’re suddenly not. Then everyone’s confused by the resignation letter.

The blamer at the dinner table becomes the manager writing perfect emails about other people’s failures. Always someone else’s fault. The team learns to hide problems rather than solve them.

The computer with their kids becomes the friend who has research for every situation but never shares their own story. You can have deep conversations about psychology. You’ll never know how they’re actually doing.

The distractor who avoids complex family topics becomes the person who hosts beautifully and never answers a direct question about themselves. Life looks perfect from the outside. Nobody’s actually close.

The congruent person becomes the colleague whom people trust with difficult news. Also, the person needs to check their volume. The one who gets thanked later and told off now.

What you might try

Pick one conversation this week. Just one. Notice which of these family communication styles you slip into when things get tense.

Not to judge it. Not to fix it immediately. Just to see it clearly.

What does that pattern protect you from? What does it cost?

Write it down somewhere you’ll see it again when the room gets loud. That’s it. No transformation required. No points for perfect execution.

Satir did real work with real families. Spent her career helping people see their patterns. I’m not recreating her system. I’m using her framework to examine my own habits. You can borrow it if it’s useful.

I’ll still get this wrong regularly. That’s fine. I’m writing this for myself first. Trying to understand why some conversations go sideways. Trying to do slightly better next time. You’re welcome to follow along.