The Star of Bethlehem has occupied my mental space for years. Not religious devotion. Curiosity about the intersection.

Where does ancient text meet observable astronomy? When does a symbol become history? How do you separate what might have happened from what people needed to believe happened?

Reading led me to more reading. Articles on conjunctions. Papers on comet orbits. Biblical scholarship on Matthew’s sources. Astronomical software reconstructing ancient skies. Each answer spawned three questions.

The rabbit hole deepened.

Chinese records. Astrological geography. Hebrew prophecy patterns. Orbital mechanics. Translation forks in Greek manuscripts. Constraint-building from minimal data.

This wasn’t casual interest anymore. It became an investigation.

Why write it up? Because the Star of Bethlehem question sits at a rare crossroads. Science can test claims. History can provide boundaries. Textual analysis can reveal patterns. Yet none fully answers what happened or what it meant. And the Star of Bethlehem is an evergreen topic year-on-year.

That tension deserves exploration beyond dismissal or devotion.

This post synthesises what testing reveals. Not to prove certainty. Not to force conclusions. To examine what’s plausible, what’s unknowable, and where different domains of inquiry reach their limits.

The investigation starts with why we are all intrigued by the Star of Bethlehem.

Why a “Star” Can Still Stop a Modern Reader in Their Tracks

Some stories refuse to fade. The Star of Bethlehem sits at that strange intersection where ancient texts meet modern curiosity, where faith bumps against astronomy, where cultural memory meets Google autocomplete. It shouldn’t still matter. Yet every December, millions search for it.

The question isn’t whether people remember the story. The question is: why do they keep asking about it?

The Data Doesn’t Lie: December After December

Search behaviour reveals what surveys and polls cannot. People don’t just recognise the Star of Bethlehem as a phrase from childhood nativity plays. They actively hunt for explanations.

The global search data pattern illustrated above shows the unbroken seasonal rhythm. Every December since 2004, searches spike sharply before dropping back to baseline. The consistency matters more than the absolute numbers. This isn’t random curiosity driven by a documentary or media cycle. It’s predictable annual resurfacing, timed to Christmas regardless of new astronomical discoveries or academic papers.

Geography reinforces the pattern. The United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and South Africa dominate searches. These regions share strong Christmas traditions and widespread English usage. The distribution stays stable year after year. Where Christmas is culturally prominent, interest in the star resurfaces at the same time of year.

The phrasing people use reveals a second layer, as the data below demonstrates. Searches for “What was the Star of Bethlehem” follow the same December peaks, showing explanatory intent rather than mere familiarity. People don’t stop at recognition. They want answers. The chart tracks identical seasonal behaviour, capturing the shift from “I know this story” to “What actually was it?”

The 2020 spike stands out. In December that year, searches hit 100 on Google’s scale. The Jupiter-Saturn conjunction (when two planets appear close together in the sky), widely publicised as the “Christmas Star”, drove extraordinary interest. Yet even without such events, the December pattern holds.

Perennial Fascination: Why It Never Goes Away

Academic attention mirrors public curiosity. Astronomers and planetarium shows revisit the star’s origins each December, reflecting sustained interest across years. The topic surfaces annually in popular culture, not as a one-time fad but as a recurring inquiry.

Experts describe the Star of Bethlehem as “a subject of perennial fascination” that draws sustained interest from both scholars and the public. This characterisation appears in formal analysis, not promotional material. The intrigue spans generations and crosses disciplinary boundaries.

Recurring does not mean stale. The question keeps resurfacing because no single answer satisfies everyone. Different camps approach the same ancient text with incompatible frameworks. That tension keeps the story alive.

Three Camps, One Story: How Interpretation Splits

1: Scientific Explanation: The Astronomical Puzzle

Some treat the star as a detective problem with a natural solution. Scholars have examined this question from a scientific perspective for decades, hunting for celestial events that fit the biblical timeline. Astronomers propose planetary alignments, comets, novae, or supernovae as possible real events behind Matthew’s account. These secular readings frame the star as an astronomical event awaiting matching to historical data.

The approach prioritises physics and observation. If something appeared in the sky circa 7-2 BCE, what celestial event fits the description? The method assumes the text references an actual phenomenon, then hunts for plausible mechanisms.

2: Biblical Scholarship: Symbolism Over Astronomy

Many biblical scholars reject the literal interpretation entirely. They see Matthew’s star as theological symbolism or a literary device, not as a report of a celestial event. Ancient literature commonly used celestial signs to mark momentous births. In this reading, the story’s purpose was never to document an astronomical occurrence.

The star functions as a narrative announcement, signalling divine involvement and kingship. Treating it as a physics problem misses the genre. The text aimed to convey meaning, not describe a sky object.

3: Faith-Based View: Miraculous Intervention

A third group maintains that the star was neither a natural event nor a mere symbol. Early theologian John Chrysostom argued the star behaved unlike any ordinary object, indicating a miraculous origin. This perspective accepts that natural explanations may be interesting but ultimately insufficient because the accurate explanation lies in divine action.

The star becomes evidence of God’s direct involvement, defying physical laws by design. Science cannot address such claims, as they operate outside empirical testing.

Active Curiosity: People Keep Asking

Contemporary astronomers report ongoing public questions about the mystery. This isn’t passive recognition. Modern audiences, not just historians or theologians, actively seek explanations. The question “What was the Star?” generates ongoing inquiry rather than settled acceptance.

The star continues to fascinate people worldwide even after two millennia. Media coverage, books, documentaries, and articles sustain broad interest. The question regularly engages both specialists and general audiences across continents.

Why Different Voices Matter

Science outlets frame the star as an astronomical mystery requiring empirical investigation. Scholars examine celestial events circa 7-2 BCE to determine what natural phenomenon could account for Matthew’s description.

Academic encyclopaedias catalogue possible explanations neutrally. Reference works list novas, comets, meteors, or planetary conjunctions as plausible candidates without endorsing any single theory. The tone stays informative, presenting multiple options as historically possible.

Faith-oriented sources take a different route. Apologetics ministries discuss scientific theories, then dismiss them as insufficient. They frame the star as direct divine action, emphasising the fulfilment of prophecy and theological purpose. The story becomes evidence strengthening belief rather than a historical puzzle.

These high-visibility perspectives (popular science, academic reference, faith-based interpretation) tell the story in fundamentally different ways. The coexistence matters. It shows why the question endures: the star sits where science, history, and religion intersect, inviting exploration from multiple angles without yielding to a single definitive answer.

What Matthew Actually Says About the Star of Bethlehem

Most discussions about the Star of Bethlehem begin with telescopes and planetary charts. That approach skips the obvious first step.

What did Matthew actually write?

The answer matters because every hypothesis about natural phenomena must fit Matthew’s account. Yet Matthew provides far less technical detail than people assume. He records a sequence of events, not an astronomy lesson.

This creates a problem. Translations don’t always agree on key phrases. Those differences determine what kind of celestial object you’re searching for.

The key phrases in Matthew 2 sit exactly where translators make judgment calls. Some read “we saw his star in the east” whilst others read “we saw his star at its rising.” That difference matters. “In the east” describes a location. “At its rising” describes astronomical behaviour.

The same applies to movement language. Some say the star “went before them,” whilst others say it “stopped” or “came to rest.” Those choices affect how strong your movement constraint becomes.

This analysis examines six independent sources. New International Version (NIV). English Standard Version (ESV). New Revised Standard Version (NRSV). King James Version (KJV). New English Translation (NET). Greek Interlinear from BibleHub.

Each represents scholarly translation work from the original Greek. Comparing them reveals where the text allows multiple readings and where it speaks with one voice. The goal isn’t an academic exercise. It’s preventing us from imposing constraints on translator interpretation rather than on Matthew’s actual wording.

The Story Matthew Tells

Matthew 2 opens with a time stamp: Jesus was born in Bethlehem during Herod’s reign. What follows unfolds as a sequence with clear narrative beats.

1: Setting

Jesus was born in Bethlehem, Judea, in the days of Herod the king.

2: Arrival

Magi from the east come to Jerusalem.

3: The Question

“Where is the one who has been born king of the Jews?” They saw his star. They came to worship.

4: Herod Disturbed

King Herod troubled. All Jerusalem with him.

5: Investigation

Herod gathers the chief priests and scribes. Asks where the Messiah should be born.

6: The Answer

Bethlehem, they reply. The prophet wrote it.

7: Secret Meeting

Herod calls the Magi secretly. Finds out the exact time the star appeared. This detail matters. It’s not casual conversation. Herod wants a timeline he can use.

8: The Mission

Herod sends them to Bethlehem. “Search carefully for the child. Report back so I may worship him also.”

9: The Journey

They leave. The star appears again. It guides them from Jerusalem to Bethlehem. Approximately 10 kilometres.

10: Termination

The star stops over where the child was.

11: Joy Response

They rejoice when they see the star.

12: Discovery

They enter the house. Find the child with Mary. Worship him. Open their treasures: gold, frankincense, myrrh.

13: Exit

Warned in a dream not to return to Herod. They leave by another route.

Context matters. Matthew 2:16 records what happens next. Herod realises the Magi deceived him. He orders the killing of all boys in Bethlehem, “two years old and under, according to the time he had learned from the Magi.”

That’s the narrative. Clean sequence. Minimal technical detail. No astronomy data.

Where The Text Splits

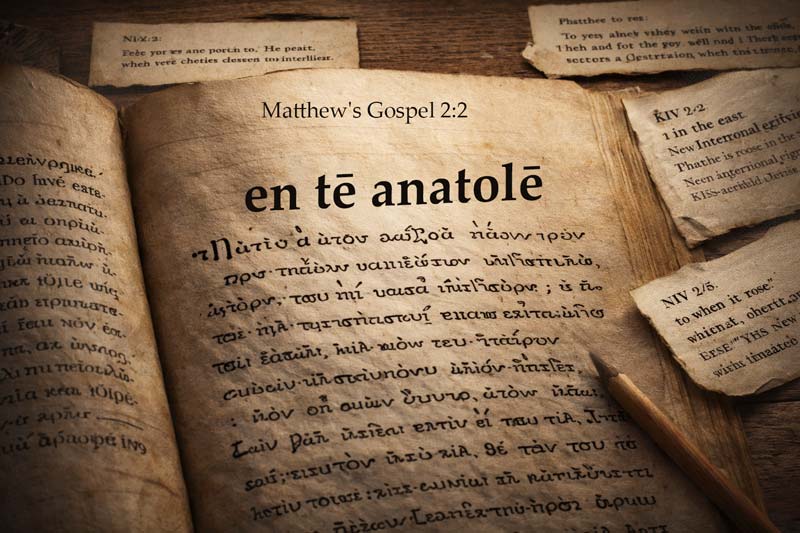

Here’s where it gets interesting. Matthew 2:2 contains a Greek phrase that translators render in two different ways.

Greek source: ἐν τῇ ἀνατολῇ (en tē anatolē)

Three translations choose one reading. Three choose another. Perfect split.

NRSV, KJV, Greek Interlinear

(geographic direction)

NIV, ESV, NET

(astronomical event)

Reading A treats it as a location. “In the east.” The Magi saw the star whilst in their eastern homeland. Geographic reference.

Reading B treats it as behaviour. “When it rose.” The Magi witnessed an astronomical event. A heliacal rising (when a celestial object first becomes visible above the horizon before sunrise).

NRSV, KJV, and the Greek Interlinear favour “in the east.” NIV, ESV, and NET favour “when it rose.”

This isn’t translator preference. It’s a fork that determines which phenomenon fits the text. Location versus astronomical action. Both readings are grammatically valid.

The visualisation above clearly demonstrates the split. Same Greek source. Two legitimate English paths.

Matthew 2:9 shows universal agreement. All six sources use guidance language. “Went before,” “went ahead,” “led them.” The star provided directional guidance on the Jerusalem-to-Bethlehem leg.

All six sources indicate termination. “Stopped,” “came to rest,” “stood over.” The Greek verb ἐστάθη (estathē) means “stood” or “came to a standstill.”

Agreement on guidance plus stopping. Disagreement on whether the initial sighting describes location or rising behaviour.

The Critical Absence

Matthew’s account contains something more important than what he includes. What he leaves out.

No mechanism. Matthew never explains what the star physically was.

No technical description. No brightness data. No colour. No size. No duration specifications.

No astronomy lesson. No orbital mechanics. No planetary positions. No celestial coordinates.

No travel time. The text doesn’t state how long the journey took.

No specific date. Only “in the days of Herod.” That’s a 33-year window from 37 to 4 BCE.

No visibility claims. Matthew doesn’t say if anyone else saw it.

No geometric detail. “Over” remains undefined. Height? Angle? Positioning? Unspecified.

No distance data. We know that Jerusalem to Bethlehem is roughly 10 kilometres from geography, not Matthew.

These absences matter. They define what constraints we can legitimately build. You can’t test hypotheses against data that Matthew never provided.

Herod’s two-year calculation tells us the star appeared long enough before the Bethlehem visit for that timeframe to make sense. But Matthew gives no more precision than that.

The star appeared at a specific, datable time. Herod asked for the “exact time.” This wasn’t a flash or momentary event. It had an observable duration.

The Magi saw it on multiple occasions. Initial sighting in 2:2. Reappearance in 2:9-10. Guidance plus joy when they see it again.

That’s the sum total. Sequence, timing bracket, reappearance, guidance language, termination behaviour. The fork on location versus rising. Universal silence on the mechanism and technical specifications.

Matthew wrote a theological narrative, not an observational astronomy report. The next question becomes: can we extract testable constraints from this minimal data?

Turning the Text into Constraints (Date, Movement, Visibility, Intent)

Constraints stop goalposts from moving. Without them, every hypothesis fits because nothing is tested correctly.

Matthew’s account contains minimal data. But minimal doesn’t mean useless. The text provides boundaries. Some are hard. Some are soft. The difference matters.

A hard constraint eliminates possibilities. Herod died in 4 BCE. Any “star” dated after that fails immediately. No interpretive wiggle room.

A soft constraint depends on which reading you take. If you follow “in the east,” you’re hunting for location-based guidance. If you follow “when it rose,” you’re hunting for rising behaviour. Both are legitimate. Both narrow the field differently.

The goal here isn’t proving anything. It’s defining what the Star of Bethlehem must satisfy before we test natural candidates. Build the boundaries first. Test hypotheses second.

The visualisation below demonstrates how constraints work as progressive filters. Each one narrows the field of possible phenomena. Hard constraints close doors. Soft constraints open multiple paths. Together, they create the testing framework.

CELESTIAL

PHENOMENA

NATURAL

CANDIDATES

Constraint 1: Herod’s Reign Sets the Date Bracket

Matthew 2:1 anchors everything to Herod. “In the days of Herod the king.”

FORCES:

Any candidate explanation must sit within Herod’s lifetime. He ruled from 37 BCE until he died in 4 BCE. That’s your outer boundary.

ALLOWS:

The text doesn’t specify a year within that 33-year window. It doesn’t give a month. It doesn’t narrow to a season. Herod’s reign provides the bracket, not a pinpoint date.

This constraint eliminates late-dated phenomena. Anything appearing after 4 BCE can’t be Matthew’s star. But it leaves decades of possibility within Herod’s rule.

Constraint 2: The Star Appeared Before the Bethlehem Visit

Matthew 2:7 records Herod’s question. He “found out from them the exact time the star had appeared.”

FORCES:

The star appears before the final journey to Bethlehem. It’s not a flash on arrival. Herod asks for the timing because there is sufficient duration to make the question meaningful.

ALLOWS:

The text doesn’t state how long before. Days? Weeks? Months? Matthew stays silent. Duration could be brief or extended. The constraint only requires: star visible before Bethlehem leg, and datable.

Matthew 2:16 adds supporting evidence. Herod kills boys “two years old and under, according to the time he had learned from the Magi.” Two years suggests the star appeared long enough before for that calculation to make sense. But it’s Herod’s interpretation, not Matthew’s statement of fact.

Constraint 3: The Location Versus Rising Fork

Matthew 2:2 creates the translation split examined earlier. This becomes a constraint with two valid paths.

Reading A: “In the East”

NRSV, KJV, and Greek Interlinear favour this reading.

FORCES:

The Magi saw the star whilst in their eastern homeland. Geographic reference. Direction matters.

ALLOWS:

This reading doesn’t specify what kind of object. Just that they observed it from the east.

Reading B: “When It Rose”

NIV, ESV, NET favour this reading.

FORCES:

The Magi witnessed heliacal rising behaviour. The star became visible in a specific astronomical way. Rising action matters.

ALLOWS:

This reading doesn’t lock the mechanism. Multiple celestial objects exhibit rising behaviour.

You can’t pick one and ignore the other. Both are grammatically valid. Any honest investigation carries both forward. Test natural candidates against Reading A. Test them against Reading B. See which fits better. That’s how constraints work when the text allows interpretive space.

Constraint 4: Reappearance Requirement

The Magi see the star twice. Matthew 2:2 records the initial sighting. Matthew 2:9-10 records them seeing it again after leaving Herod.

FORCES:

The phenomenon must be observable on more than one occasion. Single-event objects (meteors, one-time flashes) fail this constraint.

ALLOWS:

It might be the same object seen twice. It might be narrative re-emphasis. The text presents it as seen initially, then seen again during guidance. Both readings work.

This eliminates transient phenomena. Shooting stars don’t reappear. Meteors burn once. The Star of Bethlehem required sustained or repeated visibility.

Basic Geography and Travel Logic

Jerusalem to Bethlehem. Roughly 10 kilometres. South-southwest direction. Two to three hours walking for the average person, particularly in first-century conditions with uneven terrain and no modern footpaths.

Though if you’re a bit superhuman like me (95 miles weekly, 9:25/km average pace on long walks), you’d cover it in under 90 minutes. But that’s boasting, and entirely beside the point, back to the analytical work.

The Magi leave Herod in Jerusalem. The star guides them. They reach Bethlehem. The star stops.

This matters for testing “went before them” language. Whatever guided them operated over a short distance. The journey isn’t multi-day caravan travel. It’s an afternoon walk.

Does a celestial object 150 million kilometres away provide directional guidance over 10 kilometres? Can you tell if something that distant “goes before you” versus just being visible? These questions emerge from the geography meeting text.

The constraint isn’t that the star must behave in an impossible way. The constraint is that guidance language must make sense for the distance and direction involved.

Constraint 5: Leading Language on the Final Leg

Matthew 2:9 states the star “went before them.” Universal agreement across all six sources. Guidance vocabulary.

FORCES:

Your hypothesis must account for how an object provides directional help. The text describes leading, not just visibility.

ALLOWS:

This could be a literal movement. The object changes position as it travels. Alternatively, it could be interpretive guidance. The object’s position helps confirm direction. Both readings remain live.

The soft nature of this constraint creates testing space. A conjunction low on the horizon might appear to “go before” travellers heading toward it. A comet moving through the sky might provide literal leading. The text doesn’t eliminate either possibility.

Constraint 6: Termination Behaviour at the Destination

Matthew 2:9 describes the star stopping. All six sources agree. “Stopped,” “came to rest,” “stood over.”

FORCES:

The story includes a clear endpoint cue. The star’s behaviour changes at the destination. Termination must be observable.

ALLOWS:

“Stood over where the child was” remains geometrically undefined. Height? Angle? Precision? Matthew gives no data. This could be literal positioning. It could be the appearance of stopping from the Magi’s perspective. The text supports both.

The Greek verb ἐστάθη (estathē) means stood still or came to a standstill. That’s behaviour language, not measurement.

Hard Versus Soft: What We Can Actually Test

The six constraints are split into categories.

Hard constraints that close doors:

- Herod’s reign (37-4 BCE bracket)

- Pre-Bethlehem appearance (datable, not momentary)

- Reappearance requirement (sustained or repeated visibility)

Soft constraints that open paths:

- Location versus rising fork (two valid readings)

- Guidance interpretation (literal or directional aid)

- Stopping interpretation (positioned or appeared to stop)

Hard constraints eliminate candidates that fall outside boundaries. Soft constraints create testing flexibility. Both matter. Hard constraints without soft ones eliminate everything. Soft constraints without hard ones eliminate nothing.

Natural phenomena get tested against this framework. Jupiter-Saturn conjunction? Test it. Nova event? Test it. Comet passage? Test it. Chinese astronomical records? Test them.

Each candidate faces the same question set. Does it fit the date bracket? Can it account for reappearance? Does it work better with “in the east” or “when it rose”? Can guidance language make sense? Does termination behaviour fit?

The constraint set doesn’t prove any answer. It defines what counts as a plausible fit versus what fails on basic requirements. That’s the difference between testing and guessing.

Testing the Star of Bethlehem Against the Main Natural Candidates

Constraints built. Boundaries set. Now comes testing.

The previous section established six requirements any Star of Bethlehem hypothesis must address. Three hard. Three soft. Together, they create the framework.

This section tests natural candidates against that framework. Planetary conjunctions. Comets. Novas. Astrology interpretations. Each gets measured against the same constraint set.

No hypothesis will score perfectly. Matthew’s minimal data guarantees interpretive space. The goal isn’t proving certainty. It’s identifying which explanations fit better and which fail basic requirements.

The constraint test grid below shows how each candidate performs across all six boundaries simultaneously. Green marks pass. Red marks fail. Yellow marks uncertain.

(37-4 BCE)

Appearance

Rising Fork

Requirement

Language

Behaviour

Jupiter-Saturn Triple Conjunction (7 BCE): Plausible but Problematic

The Claim:

Jupiter and Saturn met three times in Pisces during 7 BCE. The planets appeared close in the sky as they moved through retrograde motion.

Date: 7 BCE

Duration: Multiple encounters over months

Visibility: Both planets are bright and observable

CONSTRAINT SCORECARD:

✓ Herod’s Reign – 7 BCE sits comfortably within the bracket

✓ Pre-Bethlehem Appearance – Duration works

✓ Reappearance – Three separate conjunctions provide multiple sightings

✗ Guidance Language – Planets 150 million km away can’t guide a 10 km journey

✗ Single Object – Conjunctions weren’t close enough to appear merged

? Translation Fork – Works better with “in the east” reading

The Evidence:

Astronomical software confirms three close approaches. “In the year 7 B.C., Jupiter and Saturn had three conjunctions in the same constellation, Pisces.” The timing attracted attention centuries ago. A note from 1285 CE pointed out this alignment coinciding with Jesus’ birth.

Johannes Kepler proposed this explanation in the 17th century. The idea persists because the timing fits and the rarity holds significance.

Why It Struggles:

The planets never appeared close enough to merge into a single object. Ancient astronomers knew their planets well. Calling a conjunction of two planets a “star” stretches credibility.

The guidance problem remains unsolved. How does an object millions of kilometres distant provide directional help over 10 kilometres? “You can’t follow a star from Baghdad to Jerusalem to Bethlehem. Stars don’t do that.”

The conjunction offers timing and rarity. It fails on the mechanism and guidance.

Jupiter-Venus Close Conjunction (3 BCE): Bright but Late

The Claim:

Jupiter and Venus came within a 1/10th degree separation. They appeared almost merged in the dawn sky.

Date: August 12, 3 BCE

Duration: Extended encounters over the following year

Visibility: Exceptionally bright, would dominate the sky

CONSTRAINT SCORECARD:

? Herod’s Reign – 3 BCE pushes date limit (Herod died 4 BCE)

✓ Pre-Bethlehem Appearance – Multiple encounters over the year

✓ Reappearance – Venus and Jupiter met repeatedly

✓ Brightness – 1/10th degree separation is highly visible

✗ Guidance Problem – Same issue as triple conjunction

✗ Multiple Objects – Two planets, not a single star

The Evidence:

The separation matched December 2020’s “Christmas Star” conjunction. “On the morning of August 12 in 3 B.C., Jupiter and Venus would’ve sat just 1/10th a degree apart in the dawn sky. That’s one-fifth the diameter of the Full Moon.”

Brightness worked. Timing worked for extended observation. The problems lie elsewhere.

Why It Struggles:

Herod’s death in 4 BCE creates dating tension. Three BCE pushes the boundary. Ancient people knew planets from stars. Two bright objects appearing close together don’t merge into a single star in the eyes of experienced observers.

The guidance language remains unexplained. Brightness alone doesn’t solve directional leading over a short distance.

Multi-Body Alignment (Jupiter-Saturn-Moon-Sun in Aries, 6 BCE): Retrograde Explanation

The Claim:

Complex alignment involving Jupiter, Saturn, the moon and the sun in Aries. Jupiter’s retrograde motion could explain “stopped” language.

Date: April 17, 6 BCE

Duration: Retrograde motion provides extended visibility

Visibility: Morning star rising in the east

CONSTRAINT SCORECARD:

✓ Herod’s Reign – 6 BCE firmly in bracket

✓ Morning Star – Aligns with dawn rising

✓ Stopped Language – Retrograde motion appears as stopping

✓ Reappearance – Visible over an extended period

? Translation Fork – Works with “when it rose” reading

✗ Requires Astrology – Multiple objects need interpretation

The Evidence:

This alignment attracted modern attention for retrograde behaviour. “Normally, planets move eastward if you’re following them in the sky. But when they go through retrograde motion, they turn around.”

Jupiter appears to stop, reverse, and stop again. That behaviour could explain Matthew’s “stood over” language without requiring a miracle.

Why It Struggles:

Multiple objects require an astrological reading. The Magi would need to interpret complex sky positions as a single meaningful event. That’s possible given their profession. But it shifts the explanation from the physical star to a symbolic interpretation.

The hypothesis holds if the Magi were astrologers interpreting the signs of the sky. It fails if Matthew describes a single bright object.

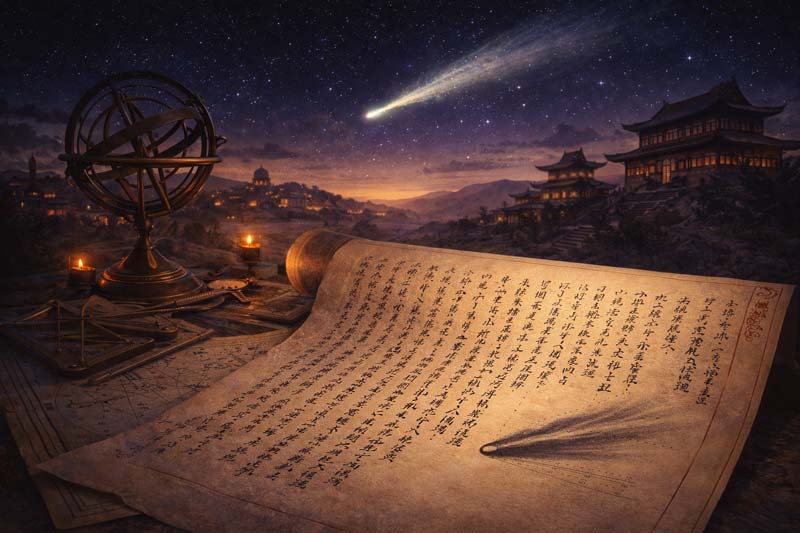

5 BCE Chinese “Broom Star”: The Comet Question

The Claim:

Chinese astronomers recorded a comet in 5 BCE. Comets move through the sky, potentially explaining guidance language.

Date: 5 BCE

Duration: Weeks to months (typical comet visibility)

Physical Record: Chinese astronomical records

CONSTRAINT SCORECARD:

✓ Herod’s Reign – 5 BCE fits the bracket

✓ Duration – Comets are visible for extended periods

✓ Movement – Could explain “went before them” literally

✓ Physical Evidence – Chinese records provide documentation

✗ Cultural Problem – Comets signified doom, not birth

? Translation Fork – Movement works with either reading

Brief Assessment:

The 5 BCE Chinese record appears across multiple sources. Comet movement could solve guidance language where static objects fail.

The cultural problem looms large. “In those days, comets up in the sky were usually a harbinger of impending disaster.” Would the Magi interpret a doom omen as a saviour’s birth sign?

This candidate deserves a detailed examination. The following section analyses the Chinese records, recent comet modelling and what they might change about plausibility. For now, the comet remains viable but culturally problematic.

Nova or Supernova: Eliminated on Evidence

The Claim:

A stellar explosion created a bright new “star” in the sky.

Date: No viable candidate exists

Evidence: Chinese records show a supernova in 185 CE only

CONSTRAINT SCORECARD:

✗ Timing – No supernova at the relevant date

✗ Physical Evidence – No remnant found from the required period

✗ Historical Records – Chinese astronomers recorded nothing at the right time

Quick Elimination:

Supernovae leave detectable remnants. “There is also no known supernova remnant, which we would expect to find if there had been a supernova at this time.”

The only recorded supernova during this era happened in 185 CE. That’s 180 years too late.

This hypothesis fails on basic evidence. No contemporary records. No physical remnant. Wrong timing entirely.

Astrology Interpretation: Reading the Whole Sky

The Claim:

The Magi interpreted multiple sky signs collectively. No single object. Astrological reading of planetary positions and alignments.

Date: Various alignments 6-2 BCE

Method: Sky reading rather than following a single star

CONSTRAINT SCORECARD:

✓ Magi Profession – Described as astrologers

✓ Asking Herod – Explains needing directions despite “star”

✓ Multiple Sightings – Different alignments over time

✓ Cultural Context – Astrology is widely practised

✗ “Stood Over” Language – Difficult to explain with interpretation

? Star Description – Matthew uses a singular star, not sky signs

The Evidence:

Modern astronomers acknowledge that historical context matters. “Astrology was a big deal back then. The explanation I have found that makes the most sense is that it was astrological.”

The Magi asking Herod for directions supports this. If following a single bright object, why ask? Astrological reading requires interpretation, not simple observation.

Why It Struggles:

Matthew describes a singular star repeatedly. The text never suggests multiple objects or complex interpretation. That could be narrative simplification. Or it could mean Matthew intended a single phenomenon.

“Stood over where the child was” proves harder to explain through astrology than through physical object behaviour.

What the Testing Reveals

Five candidates tested. One (nova/supernova) was eliminated entirely. Four remain plausible with varying problems.

Best fits for hard constraints:

- Triple conjunction (7 BCE): Timing, duration, reappearance

- Multi-body alignment (6 BCE): Retrograde explains stopping

Best potential for guidance:

- 5 BCE comet: Literal movement through the sky

- Astrology: Interpretation rather than following

Weakest overall:

- Jupiter-Venus (3 BCE): Dating problem with Herod’s death

No candidate passes all constraints cleanly. The triple conjunction scores well on timing but fails guidance. The comet solves movement but fails in a cultural context. Astrology explains asking Herod but struggles with “stood over.”

The constraint framework narrows possibilities. It eliminates some options. It exposes problems in others. What it can’t do is prove any single answer.

Matthew’s minimal data deliberately or accidentally preserves interpretive space. Science can clarify what’s plausible. It can’t determine what happened.

The following section examines one candidate in greater depth: the 5 BCE comet and new modelling claims about its behaviour.

What the 5 BCE Chinese Records Might Change About the Star of Bethlehem

The previous section flagged one candidate for closer examination. The 5 BCE comet.

Chinese astronomers recorded it. The timing fits Herod’s bracket. Duration works. Movement could solve guidance language where static objects fail.

But the cultural problem loomed. Comets signified doom. Why would the Magi read doom as birth?

A 2025 paper in the Journal of the British Astronomical Association changes the conversation. Not by solving the cultural problem. By demonstrating something no previous Star of Bethlehem hypothesis addressed.

A comet orbit that could make “went before them” and “stood over” physically plausible.

The Chinese Record: What They Saw

Han Shu: Tianwen Zhi, chapter 26, preserves the observation. “2nd year, 2nd month; a broom star emerged in Ch’ien Niu for over 70 days.”

The second month of the second year falls between March 9 and April 6, 5 BCE. That falls within Jesus’ birth window. The object remained visible for over 70 days.

Ch’ien Niu is a Chinese constellation near Capricornus. The region sits close to the ecliptic (the Sun’s path across the sky). The name also refers to the ninth Lunar Mansion, spanning roughly 8 degrees.

According to Ho (1966), Ch’ien Niu once referred to the constellation including the stars β, α, and γ Aquilae. Still, during the Han dynasty period, Altair and these stars were known separately as Ho Ku.

“Hui hsing” means broom star. Chinese taxonomy for tailed comets. The Han Shu describes the typical hui hsing appearance: “Its body is like a star. Its end is like a broom. It is 2 zhang long.” That’s approximately 20 degrees of tail length.

The Mawangdui Han dynasty tombs preserve a “Cometary Atlas” from 168 BCE showing hui hsing diagrams. Tailed objects. Comets.

The record is clear. Chinese astronomers called it a comet.

The Debate: Comet or Nova?

Despite the broom star classification, some scholars questioned the identification. Hughes (1979) and Kidger (1999) challenged whether it was actually a comet.

Comets typically move through constellations over days or weeks. They don’t stay in one region for 70+ days.

That extended visibility in the same sky region prompted speculation. Maybe it was a bright nova or supernova instead.

But comets can appear stationary under specific circumstances. Aircraft pilots know the principle. If an object’s angular position doesn’t change relative to a moving observer, the object travels directly toward or away from that observer.

Apply that to a comet. If it’s heading almost directly toward Earth, it appears to stay in one constellation region despite actual movement through space.

The 70-day observation of Ch’ien Niu could indicate orbital geometry rather than object type.

Humphreys (1991) identified Capricornus as matching the Greek astrological geography map, with astronomical events in that region associated with Syria.

What Matney’s Model Claims to Solve

The 2025 study introduces computational orbit modelling to the Star of Bethlehem question. The approach uses the Chinese observations to constrain possible comet trajectories.

The claim: a comet orbit exists that passes very close to Earth in early June 5 BCE, exhibiting temporary geosynchronous motion.

Geosynchronous (meaning the comet moves with Earth’s rotation) means the comet could appear to pause in the sky as seen from Judea. That behaviour would be visible, extraordinary and recognised by trained observers.

This represents the first astronomical candidate ever identified that could physically match Matthew’s “went before” and “stood over” language.

Not through vague interpretation. Through specific orbital mechanics, producing observable behaviour.

The June 8 Mechanism: Hour by Hour

The modelled orbit puts the closest approach on June 8, 5 BCE. Distance: 0.0026 astronomical units. Roughly Earth-Moon separation.

The timeline below demonstrates how the comet’s motion would appear from Bethlehem throughout that morning.

June 7

June 8

Motion cancels rotation

Almost overhead

Noon

Lost in glare

Evening, June 7 (~22:00 local time):

Comet rises. Visible through the night.

Dawn, June 8 (~05:00):

The sun rises. Comet sits at azimuth just west of south.

Mid-morning (~08:00):

Comet reaches its closest distance to Earth. Its angular motion against background stars accelerates eastward. That acceleration approximately cancels out Earth’s rotation.

The result: the comet appears to pause in azimuth as seen from Judea.

Late morning (~10:00):

The comet reaches near zenith. Almost exactly overhead. It pauses there until around 11:30. During this temporary geosynchronous period, the comet remains virtually motionless over Bethlehem.

Noon:

The comet resumes westward diurnal motion. Follows the Sun across the sky. Likely lost in solar glare until setting shortly after sunset.

The azimuth alignment matters. The Jerusalem-Bethlehem line runs roughly 206° azimuth. The comet’s azimuth remained within a few degrees of that line throughout the morning.

A traveller walking from Jerusalem to Bethlehem would see the comet directly ahead. Arriving in Bethlehem around 10:00, they’d see it stop almost overhead for approximately two hours.

That’s the mechanism. Geometry plus orbital mechanics produces observable guidance behaviour.

What the Model Requires to Work

The analysis revealing June 8 behaviour isn’t unique. Multiple orbital solutions fit the Chinese observations whilst exhibiting similar motion patterns. These orbits have shifted perihelion dates and nodes, but produce the same close-approach behaviour on different dates.

Matney’s numerical model optimised a cometary orbit consistent with 5 BCE observations. The method assumed a parabolic orbit (standard for long-period comets). Position and velocity defined the state vector at the chosen reference time.

Uncertainty remains throughout:

The Chinese observations constrain location only within ±10 degrees. Only the month is known, not the precise initial sighting day.

The model employed Monte Carlo sampling (a method that uses lots of random samples to estimate an answer when exact calculation is hard). The initial observation date was chosen randomly from March 9 through April 6. Three sample dates represented the 70-day visibility window.

Ch’ien Niu’s extent is somewhat subjective. The model defined a box spanning 270-280 degrees ecliptic longitude and -5 to 10 degrees latitude. Random points chosen within that box for each sample date.

The method differs from standard orbit determination. No analytic estimate required. Just the initial state vector and optimisation method.

Critical assumption:

The orbit must bring the comet within roughly 1 million kilometres of Earth. Extremely close. Rare geometry. Required for temporary geosynchronous motion to occur.

That’s not a small requirement. It’s the mechanism’s foundation.

What Changes and What Doesn’t

The 5 BCE comet gains mechanical plausibility. A physical explanation now exists for guidance and stopping language that doesn’t require a miracle or symbolic interpretation.

But limits remain clear.

The model produces a family of orbits rather than a unique solution. Multiple dates work if the geometry aligns correctly. June 8 isn’t proven. It’s modelled as possible.

The Chinese record uncertainty persists. ±10 degrees position. Unknown exact day. Those margins allow computational flexibility but prevent definitive claims.

The cultural problem hasn’t disappeared. Comets still represented doom in ancient worldviews. The Magi’s interpretation of a disaster omen as a birth sign remains unexplained by orbital mechanics.

No Western record confirms the observation. Only Chinese sources document this object. That asymmetry doesn’t eliminate the comet. It limits confidence.

What Matney demonstrates: if the 5 BCE object was a comet, and if its orbit brought it extremely close to Earth at the right moment, then guidance and stopping behaviour become physically possible rather than symbolically necessary.

That shifts constraint testing. The comet candidate strengthens its mechanism whilst maintaining cultural and evidential weaknesses.

The following section examines where science stops, and other questions begin.

When Science Runs Out: Symbolism, Meaning, and the Possibility of the Miraculous

The previous sections tested natural explanations against historical constraints. Comets. Conjunctions. Astronomical models. Each scored differently. None proved certain.

But testing physical mechanisms addresses only half the question. The other half lives in a different domain entirely.

Finding the Patterns: A Technical Note

This section required extracting biblical verses connected to the Star of Bethlehem through a thematic pattern rather than explicit mention. A Python script filtered the NIV Bible using specific trigger and context terms.

Trigger terms: star, stars, light, brightness, dawn, shine, arise, glory, sign.

Context terms: Bethlehem, born, birth, child, king, Messiah, Magi, wise men, east, gold, frankincense, myrrh, gift, worship, Jacob, Israel, sceptre, nations, Gentiles.

Exclusion terms: create, creation, firmament, sun, moon, seasons, heaven’s host.

The filter removed cosmological noise. Genesis creation accounts dropped. Stellar creation passages excluded. What remained: verses ancient readers might have connected to Matthew’s narrative through symbolic echo.

The extraction revealed patterns.

The Star as King: Numbers 24:17

Seven centuries before Jesus’ birth, Balaam spoke prophecy over Israel. “I see him, but not now; I behold him, but not near. A star will come out of Jacob; a sceptre will rise out of Israel.”

The parallelism establishes equivalence. Star equals sceptre. Both symbolise a ruler. The verse doesn’t describe astronomy. It describes kingship through celestial metaphor.

Ancient readers trained in Hebrew poetry would recognise the pattern immediately. Star language signals royal authority.

When Matthew records the Magi asking, “Where is the one who has been born king of the Jews? We saw his star when it rose,” the echo would resonate.

Numbers 24:17 provided a template. Matthew’s star invoked that template.

Isaiah’s Light Architecture: Nations Coming to Brightness

Isaiah 60 builds an elaborate pattern around light, nations, kings and gifts.

“Arise, shine, for your light has come, and the glory of the LORD rises upon you.” Darkness covers the earth. But light rises. “Nations will come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn.”

The next verses specify: “All assemble and come to you; your sons come from afar.” Then the gift catalogue: “Herds of camels will cover your land, young camels of Midian and Ephah. And all from Sheba will come, bearing gold and incense and proclaiming the praise of the LORD.”

Gold. Incense. Nations coming. Kings approaching light.

The pattern web below demonstrates how Matthew’s narrative connects to these prophetic frameworks through shared vocabulary and structure.

Isaiah 60 wasn’t predicting an astronomical event. It described Jerusalem’s restoration through imagery of light attracting distant peoples and their wealth.

But Matthew’s account triggers the same vocabulary cluster. Light/star. Kings/Magi. Coming from the east. Gold and incense. The textual echo would be unmistakable to readers familiar with Isaiah.

Psalm 72: Kings Bringing Tribute

Psalm 72 adds another layer. “May the kings of Tarshish and of distant shores bring tribute to him. May the kings of Sheba and Seba present him gifts. May all kings bow down to him and all nations serve him.”

Kings. Distant locations. Gifts. Worship.

Matthew’s Magi come from the east. They bring gold, frankincense, and myrrh. They bow down and worship.

The psalm describes ideal kingship. Matthew’s narrative embodies the pattern.

The Sign Language: Isaiah and Luke

Isaiah 7:14 introduces sign vocabulary around birth. “Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign: The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel.”

Sign. Birth. Son.

Luke 2:12 employs an identical framework. “This will be a sign to you: You will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.”

Matthew doesn’t explicitly use “sign” language for the star. But readers connecting Matthew’s account to Isaiah 60 and Luke’s angels would recognise a pattern of signs operating throughout nativity narratives.

Signs announce arrival. Stars in Matthew. Angels in Luke. Both function as heavenly announcement mechanisms.

Light for the Gentiles: The Outsider Pattern

Luke 1:78-79 describes “the rising sun” coming “from heaven to shine on those living in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the path of peace.”

Rising sun. Light in darkness. Guidance.

Simeon’s prophecy in Luke 2:32 identifies the child as “a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and the glory of your people Israel.”

The Magi represent Gentile inclusion. They’re outsiders. Non-Jews. Following a celestial phenomenon to worship the Jewish king.

Isaiah 49:6 had established a framework: “I will also make you a light for the Gentiles, that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth.”

Matthew’s star draws Gentiles to Israel’s king. The pattern fulfils Isaiah’s outsider-inclusion theme.

How Early Readers Understood the Star of Bethlehem

First-century readers didn’t separate literal from symbolic the way modern readers do. The categories weren’t mutually exclusive.

A physical astronomical event could simultaneously carry symbolic meaning. Natural phenomena could function as a divine sign. The question wasn’t “real star or metaphor?” The question was “What does this event signify?”

Matthew’s audience, saturated in Hebrew scripture, would hear the textual echoes. Star language invoked Numbers 24:17. Kings and gifts triggered Isaiah 60. Gentile inclusion resonated with Isaiah’s light-for-nations theme.

Whether the star was a comet, conjunction, or miracle became secondary to the pattern recognition. The narrative worked by accumulating prophetic resonances.

That doesn’t mean early readers rejected astronomical reality. It means they read events through the interpretive frameworks provided by their scriptures.

Where Mechanism Ends, and Meaning Begins

Scientific analysis can identify plausible astronomical candidates. It can model comet orbits. It can calculate conjunction dates. It can test hypotheses against historical constraints.

What science cannot do: determine whether an event carried divine intention. Assess symbolic significance. Prove or disprove the theological meaning.

The 5 BCE comet might have exhibited temporary geosynchronous motion. That’s a testable claim about orbital mechanics. Whether God directed that comet to guide the Magi is a question entirely different.

Ancient astrology interpretation might explain the Magi’s behaviour. That’s a historical and cultural claim about how people read sky events. Whether the sky reading was divinely orchestrated addresses theological territory.

The mechanism vs meaning split isn’t a weakness. It’s boundary recognition.

Natural explanations can illuminate how something might have happened physically. They can’t explain why it mattered theologically or what it symbolised.

The Miraculous Possibility

Honesty requires acknowledging that the Star of Bethlehem could have been a miracle with no natural explanation.

All astronomical hypotheses assume a natural cause. That assumption makes scientific investigation possible. But it doesn’t make miracles impossible.

A supernatural event wouldn’t leave testable astronomical evidence. It wouldn’t be constrained to known orbital mechanics. It wouldn’t require Chinese records or conjunction calculations.

The absence of a perfect natural explanation doesn’t prove a miracle. The presence of a plausible natural explanation doesn’t disprove a miracle.

Both possibilities remain open.

What the Patterns Reveal

The biblical texts connected to Matthew’s star don’t primarily concern astronomy. They concern kingship, inclusion, light, guidance, and worship.

The star functions in Matthew’s narrative as an announcement mechanism. It signals the birth of the king. It draws Gentiles to worship. It fulfils prophetic patterns about nations coming to Israel’s light.

Whether that announcement required a comet, a conjunction, an astrological reading, or a miraculous phenomenon, the text doesn’t specify a mechanism. It specifies meaning.

Numbers 24:17 made the star language royal. Isaiah 60 made light language about nations gathering. Psalm 72 made bringing gifts normative for an ideal ruler.

Matthew’s account accumulates these patterns. The astronomical question becomes: did a natural event provide the framework for Matthew’s interpretation? Or did Matthew construct narrative from prophetic templates regardless of astronomical reality?

Science can’t answer that question. Historical analysis can’t answer that question. Textual pattern recognition reveals that the question exists.

The following section examines what we can say with confidence and what remains genuinely unknowable.

What We Can Say with Confidence and What We Can’t

Six sections tested the Star of Bethlehem against constraints, candidates, Chinese records, and prophetic patterns. Some questions were narrowed. Others widened.

What the Evidence Supports

Matthew’s text establishes firm boundaries. Herod’s reign brackets dates. Duration language requires a datable event, not a momentary flash. The reappearance requirement eliminates single-observation phenomena.

The translation fork matters. “In the east” versus “when it rose” creates two testable paths. Neither proves correct. Both remain grammatically valid.

Chinese records document Hui Hsing in 5 BCE. March through June visibility. Ch’ien Niu constellation location. The taxonomy clearly identifies a comet, despite scholarly debate.

Matney’s orbital model demonstrates that temporary geosynchronous motion is mechanically possible. Not proven. Possible. That shifts the comet hypothesis from culturally problematic to physically plausible.

Pattern recognition reveals how ancient readers connected texts. Numbers 24:17 made the star language royal. Isaiah 60 built a light-attracts-nations framework. Matthew’s account triggers multiple prophetic echoes simultaneously.

These aren’t speculations. They’re documentable observations about text, astronomy, and historical records.

Best-Fitting Natural Candidates

Three candidates perform better than the others in constraint testing.

5 BCE comet: Passes Herod bracket, duration, reappearance, physical record. Matney model provides a guidance mechanism. Cultural doom-omen problem persists. The model produces a family of orbits rather than a unique solution.

Multi-body alignment (6 BCE): Jupiter-Saturn-Moon-Sun in Aries. Retrograde explains “stopped” language. Morning star timing works. Requires astrological interpretation. Multiple objects, not a single star.

Triple conjunction (7 BCE): Jupiter-Saturn in Pisces. Three encounters provide reappearance. Timing solid. Fails guidance language. Too distant for directional leading.

None scores perfectly. Each explains some constraints whilst struggling with others.

What Remains Genuinely Unknowable

No natural candidate can be proven correct. The data margins prevent certainty.

Matthew provides minimal astronomical detail. No colour. No brightness. No specific date beyond “days of Herod.” No mechanism. No visibility to others confirmed.

Chinese records constrain location within ±10 degrees. Month known, exact day unknown. Western sources don’t confirm the observation.

Whether the Magi interpreted the doom comet as a birth sign: culturally implausible but historically unprovable. People do unexpected things under conviction.

Whether a natural event carried a divine intention is untestable by any method. The mechanism doesn’t address meaning. Physics doesn’t determine theology.

Whether Matthew constructed a narrative from prophetic patterns without astronomical events: possible but unverifiable. The textual echoes exist regardless.

The Star of Bethlehem might have been a miracle with no natural explanation. That possibility can’t be eliminated through astronomical testing.

What the Investigation Taught

Constraint-building reveals more than candidate-testing. How you frame questions determines which answers become visible.

The translation fork in Matthew 2:2 opens investigation paths modern readers miss. Ancient astronomy was sophisticated. Chinese records provide independent documentation. Orbital mechanics can produce extraordinary behaviours.

Symbolic meaning doesn’t require literal astronomy. But literal astronomy doesn’t eliminate symbolic meaning. The categories aren’t mutually exclusive.

First-century readers didn’t separate natural from supernatural the way contemporary minds do. A physical comet could function as a divine sign. Astrological reading could reveal theological truth. The framework allowed both simultaneously.

Testing natural hypotheses illuminates what’s plausible without proving what happened. That’s not failure. That’s appropriate boundary recognition.

The Question That Persists

After examining translations, testing candidates, modelling orbits, and tracing prophetic patterns, one thing becomes clear.

The Star of Bethlehem worked.

Not astronomically. Narratively.

It drew Gentiles to worship the Jewish king. It announced birth through a heavenly sign. It fulfilled prophetic templates about light-attracting nations. It triggered recognition in readers saturated with Hebrew scripture.

Whether it worked because Matthew witnessed an astronomical event and interpreted it through prophecy, or because Matthew constructed an account from prophetic patterns regardless of astronomy, the text doesn’t answer that question.

It wasn’t written to.

Matthew’s purpose was theological announcement, not astronomical documentation. The star functions in the narrative as a sign. Signs point beyond themselves.

Perhaps the deepest insight isn’t about what the star was. It’s about what questions ancient texts were written to answer versus what questions modern readers bring to them.

The investigation taught me humility. Not the false humility that dismisses inquiry. The earned humility that recognises where certainty ends, and interpretation begins.

Some questions deserve pursuit without expecting resolution. Every December, the pattern repeats. New readers discover the puzzle, run the exact searches, and hit the same boundaries. The star rises annually in search data because the question refuses to settle.

Analysis complete. Now test it yourself. Four interactive tools for the Star of Bethlehem: compare translations, build constraints, track the comet timeline, and map prophetic patterns. Your hands on the data.

Sources

- Betz, E. (2023). The Star of Bethlehem: Can science explain what it really was? Astronomy.

- Britannica Editors. Star of Bethlehem Celestial Phenomenon.

- Eric Betz. The Star of Bethlehem: Can science explain what it really was? December 24, 2023. Astronomy.

- Fletcher, H. What was the Star of Bethlehem? University of Cambridge.

- Ho, P. Y. (1966). The astronomical chapters of the Chin Shu. Mouton.

- Hughes, D. W. (1976). The Star of Bethlehem. Nature, 264, 513–517.

- Hughes, D. (1979). The Star of Bethlehem: An Astronomer’s Confirmation. Walker and Company.

- Humphreys, C. J. (1991). The star of Bethlehem, a comet in 5 BC and the date of the birth of Christ. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, 32, 389-407.

- Kidger, M. R. (1999). The Star of Bethlehem: An astronomer’s view. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05823-8.

- Matney, Mark. (2025). The star that stopped: The Star of Bethlehem & the comet of 5 BCE. Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 135. 387-406.

- O’Callaghan, J. (2024). What was the Star of Bethlehem? Space.

- Royal Museums Greenwich. What was the Christmas Star?